Concussion: Shifting the Paradigm

Viewing Concussion through the lens of a Neurological Network Disruption Injury.

Concussion: The Need for a Paradigm Shift

The landscape of concussion has shifted significantly in the last 50 years. Once thought of as a bell rung injury where seeing a couple of stars is normal and means the athlete can return back to competition immediately. Today, it's often seen as a purgatory, with athletes sidelined for weeks upon sustaining a concussion and clinicians advocating for a complete shutdown and rest upon the onset of symptoms. This landscape stemmed from our failure to initially recognize the seriousness of concussions, leading to instances where athletes suffered severe injuries and, sadly, sometimes even death.

The shift to purgatory occurred because if an athlete sustains a concussion and their brain hasn't fully healed, a subsequent impact increases the risk of the injury becoming more severe. This scenario is no different than playing with a partially torn ligament, where an additional impact into that tissue can lead to more significant damage. This second impact while still dealing with the effects of a concussion is often referred to as Second Impact Syndrome (SIS).1

The most recognized example of SIS is the high schooler Zackery Lystedt, who was in a coma for 31 days, unable to speak or move for 9 months, and fed through a feeding tube for 2 years. The severity of this injury could have all been avoided if he was not allowed to return to play after clear signs of a concussion were evident after a hit earlier in the game. This unfortunate event received national attention and resulted in the first state law around concussion in the state of Washington in 2009 and eventually led to a concussion law around youth sports in all 50 states.

This increase in attention has yielded several benefits, such as a significant increase in research efforts and specialized training. However, alongside these positive benefits, there are unintended consequences where fear tends to override the scientific evidence. A great example is the recent death of former NHL player Chris Simon being immediately attributed to Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). Unfortunately, these tragic events result in one particular scientific group monopolizing media attention, causing more measured explanations to be ignored and disregarded. ESPN recently acknowledged and addressed this imbalance in media coverage around CTE.2

As a clinician working directly with concussed athletes, I believe the current approach to managing this injury has swung too far towards fear. I advocate for educating athletes and practitioners on the latest scientific evidence - which will bring the pendulum back to a more balanced equilibrium.

The Evolution of Defining Concussion

Old Definition of Concussion:

While there are many definitions of concussion, these are often centered around the mechanics and do not fully encompass what the injury is and entails. The Concussion in Sport Group (CISG), in their 2017 paper, defined concussion as traumatic brain injury induced by biomechanical forces.3

Shifting the Paradigm Away From the Mechanical

I started my PhD in 2014 and began the deep dive into concussion that has become my career. In 2014 neuroscience research was becoming much more prevalent. The advancement of neuro-imaging resulted in scientists being able to attribute specific physical and cognitive processes to specific networks in the brain.4 At the same time, concussion research began to highlight several specific dysfunctions that could occur, including neurometabolic5, axonal6, cerebrovascular7, autonomic8, vestibular, and ocular-motor9. Many in the field developed the can’t see the forest for the trees phenomenon. The process of writing my dissertation in 2019 allowed me to experience that which Incubus sings about, to obtain a bird’s eye is to turn a blizzard to a breeze.

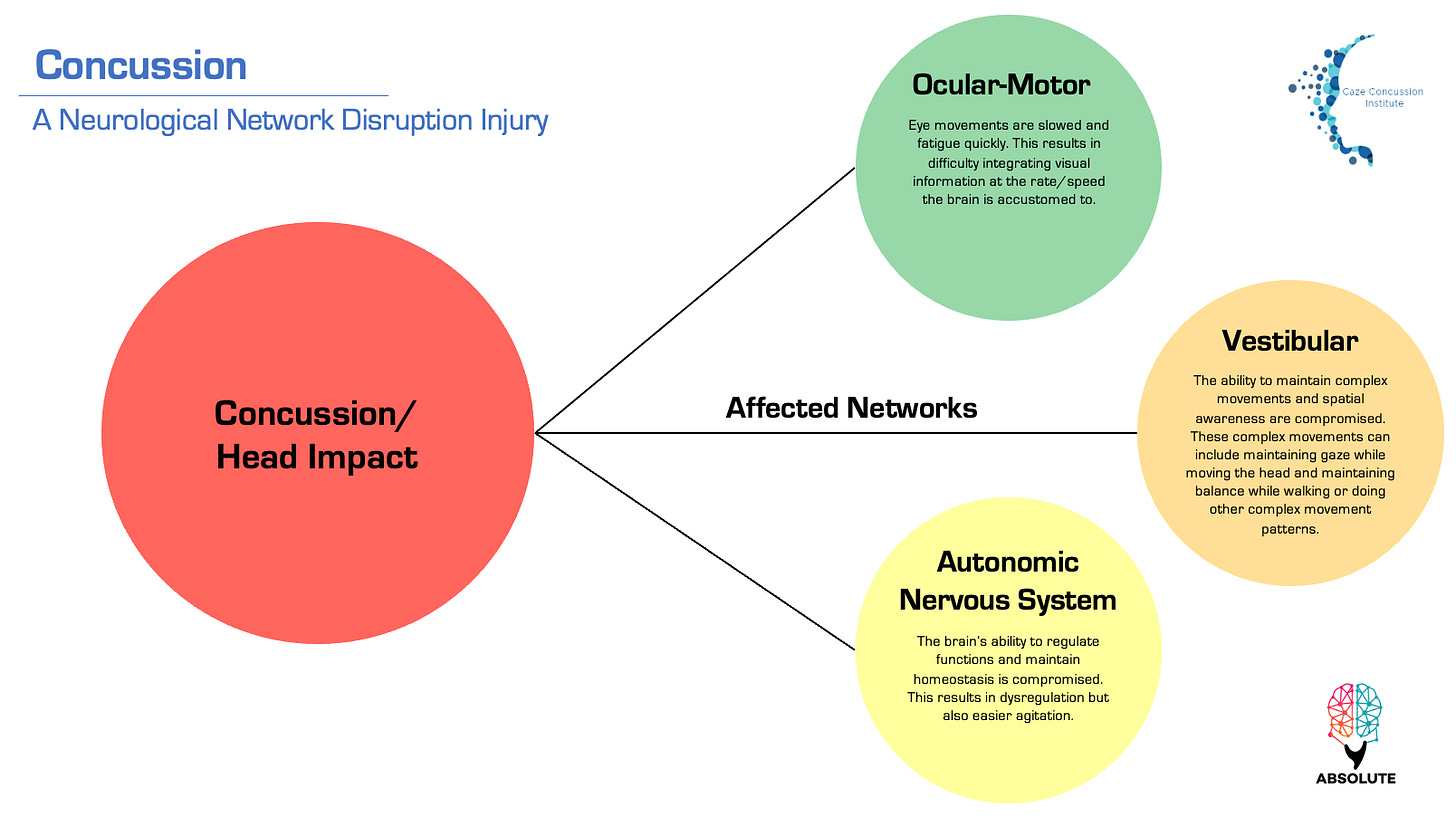

The Paradigm Shift in Definition: Concussion = A Network Disruption Injury!

In its simplest form, a concussion is a neurological network disruption injury. While the 2017 CISG definition suggested that clinical signs and symptoms are largely a reflection of functional disturbance rather than a structural injury, no one, until this point, clearly stated what concussion is in its simplest form. Said another way, the network disruption is the injury! Sitting and contemplating the nuances of the implications of this definition has led to the current paradigm shift in concussion.

Old Definition: traumatic brain injury induced by biomechanical forces.

New Definition: a neurological network disruption injury.

Implications of this New Definition

The implications of this new, more accurate definition is paradigm-shifting for both practitioners and athletes. With specific assessments allowing practitioners to identify the disrupted neurological networks in the athlete's brain, this allows them the opportunity to prescribe the appropriate constraints and work that is best for that individual athlete rather than merely sending them to purgatory.

Solving the Failures of Diagnosing Concussion in Sport

Regarding assessment, we still live in a world where we can watch on TV an athlete who clearly has signs of concussion, but yet they emerge from the blue tent, and the neuro-trauma consultant has missed the concussion. How does this occur? The issue is the consultants are using the old, traditional, and stagnated paradigm where they base their diagnosis on an over-reliance on measurement tools and/or reported symptoms.

However, if we shift the focus in the assessment to understanding the neurological networks disrupted in the brain, clinicians can mitigate their reliance on what the player verbally communicates. It is well understood that oftentimes, due to the competitive nature of players that they may provide responses that they know will allow them to return to play, potentially masking the severity of their symptoms. By prioritizing an assessment of the neurological networks that can be disrupted via concussion, clinicians can achieve a more objective assessment, reducing the likelihood of missed concussions - which is sadly commonplace.

In this new paradigm, clinicians can target specific neurological networks on assessment and provoke symptoms that should only arise if there's a disruption (i.e., injury) in those networks. This approach parallels how we don't rely solely on a player's self-reporting to diagnose an ACL tear; instead, we use tests like the Lachman Test to assess the integrity of the ACL by directly stressing the connective tissue thickening that is the ACL with a load. By doing so, the clinician is able to discern with high diagnostic certainty whether or not the ACL has been disrupted. Similarly, by provoking symptoms related to neurological networks, clinicians can obtain more objective evidence of concussion and make more accurate diagnoses and relevant clinical management decisions.

Vestibular Ocular Motor Screener

In the world of concussion, this symptom provocation assessment is the Vestibular Ocular Motor Screener (VOMS). Novice clinicians using the VOMS can effectively identify most concussions within minutes by understanding which symptoms can be provoked and how. What is fascinating is that experienced clinicians who administer the VOMS extensively become highly nuanced in their understanding of the behaviors of vestibular and ocular motor systems.

With tens of thousands of repetitions, the expert clinician understands the behavior of the vestibular and ocular motor system in such a way that the expectation of movement patterns is dependent on the athlete’s years of experience, sport, and even position. This level of reps allows the clinician to understand what the capacity of each network is across a spectrum. As a result, catching and identifying the specific disruption, as well as when it is resolved, often takes less than a minute.

Neural Networks are Trainable

Neural networks are trainable, meaning that they can be stimulated and developed over time through the appropriate training work. In other words, if a network is deemed to be disrupted and, therefore, compromised, work can be performed by the athlete to stimulate the networks redevelopment. In the same way an outward biological injury should be progressively and repeatedly stimulated at a level required to induce an adaptive response, the neurological system must also be addressed progressively so that it can itself create a progressive adaptive response that continues to further its re-configuration.

This is again where the clinician's level of experience and, more importantly, repetitions of the VOMS assessment are vital. Through this simple assessment, experienced clinicians can gain the information needed to answer complex questions regarding specific and individualized training. The expectations for ACL recovery and the level of capacity of what a fully healthy knee should do for an individual are different for an elite athlete versus a sedentary adult. The same is true for the speed at which I, as a clinician, expect the eyes to move and integrate visual information (the ocular motor system).

The Rest in Purgatory: No Training Paradigm

The controversy surrounding training protocols for concussed athletes persists, with many schools adhering to outdated guidelines requiring athletes to be symptom-free before returning to training. This approach fails to consider the fundamental role of the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) in integration with other bodily functions and to maintain homeostasis. By denying highly conditioned athletes the opportunity to train and activate/stimulate their ANS, these protocols behave as a limiting constraint on the concussed athlete. Novice clinicians who implement these antiquated practices are often surprised when their athletes develop more symptoms, mistakenly attributing it to worsening injury rather than the poor management exacerbating network disruption.

Interestingly, most people assume that the notion of light symptom provocation through physical exercise did not start getting empirically validated till after concussion laws saying no exercise if symptomatic were passed. So conservatively, in 2012, when laws were becoming more broad and sweeping across states, there was no such research. However, as early as 2007, articles advocated for light exercise and slight symptom provocation to accelerate recovery.10 This means that clinicians managing concussed athletes knew much earlier the importance of early autonomic stimulation/activation training work and were implementing it into their clinical care! Given the rigor of the scientific process and the lag between practice and publication, this has likely been practiced since the early 2000s.

The Current Big 3 Neurological Networks

The three major neurological networks that are impacted by concussion are:

Ocular-motor: helps us to control our gaze and integrate visual information. Symptoms/signs of disruption to this network include: blurred vision, headache especially, a “pressure” usually behind the eyes, light sensitivity, brain fogginess, and feeling cognitively slowed down.

Vestibular: helps us control our gaze and gait and know where we are in space. Symptoms/signs of disruption to this network include dizziness, nausea, blurred vision, balance problems, and feeling foggy.

Autonomic Nervous System: is our integration powerhouse and helps us with maintaining homeostasis. Its main role is the 4Fs: fight, flight, freeze, f@$! (or fawn). Symptoms/signs of disruption to this network include fatigue, sleep disturbance (too much or too light), exercise intolerance and/or symptoms are exacerbated with physical activity, and mood disturbance, including an increase in irritability.

The New Paradigm

The new paradigm of concussion is: What if our attention was turned to how the networks disrupted by concussion are trainable? And if they are trainable - which is the hypothesis we will argue, maybe there is a threshold of targeted training that would result in prevention or minimization of injury.

Our hypothesis is not that far-fetched. There are reasons why athletes recover faster than the general population from concussion injury. Where thinking needs to shift and where research must venture towards is what is about athletes and how they have specifically trained the networks disrupted after concussion that allows them to heal so quickly. This is where we believe the theoretical underpinnings of the Internal Strength Model can lay the foundation for this application of thought to be constructed in the world of concussion.

Todd May; Lisa A. Foris; Chester J. Donnally III, Second Impact Syndrome.

Shwetha, S. & Fainaru-Wada, M. (2024, February 1). How fears over CTE and football outpaced what researchers know.

Paul McCrory; et al., What is the definition of sports-related concussion: a systematic review.

Giza, Christopher C. MD; Hovda, David A. PhD, The New Neurometabolic Cascade of Concussion.

Grossner, E. C., Mayer, A. R., & Hillary, F. G., Neuroimaging and Sports-Related Concussion.

John J. Leddy, MD; et al., Active Rehabilitation of Concussion and Post-concussion Syndrome.

Great article 💯🙏