“Don’t be afraid to fail or look like a fool...

A story about not being afraid to look like fool and the simple heuristic of: try it first then figure out why it works second.

These are necessary milestones on your way to the top.”— Louie Simmons

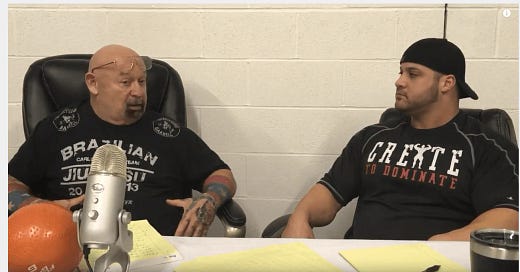

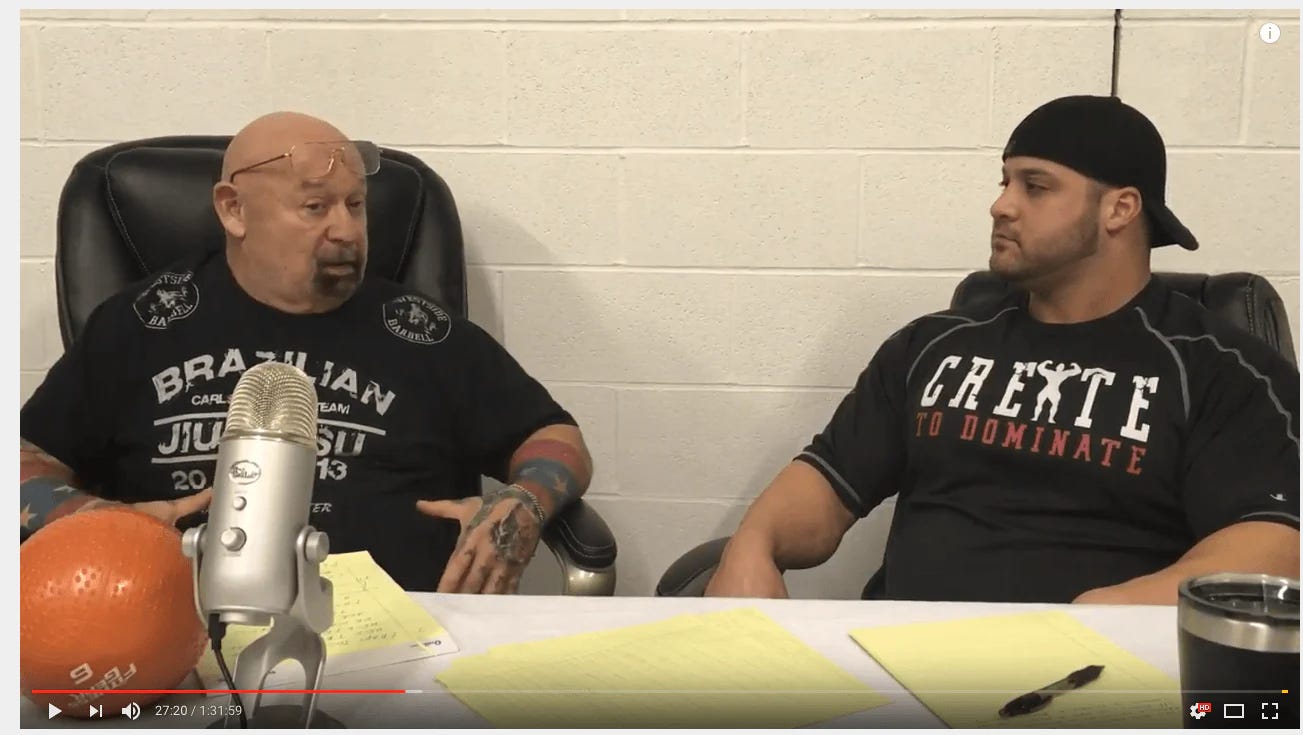

Louie Simmons, the godfather of the neurological training paradigm, was an innovator unafraid to fail or even look foolish in pursuit of progress. He and his lifters at Westside Barbell followed a simple heuristic: keep what works and throw out what doesn’t. In the video below, Jim Sietzer1—one of Louie’s first training partners and a fellow innovator of the BandBell—explains how this approach led to the BandBell’s development. This willingness to experiment, to risk failure in the pursuit of progress, was also pivotal to Westside’s pioneering use of bands over barbells. Another of Louie’s former training partners, Dave Tate, summed up Westside as functioning as: 'try it first, then figure out why it works second.'

A Bodybuilder at a Raw Bench Press Meet

I was fortunate that Louie was open-minded enough to let me into the club—to treat him and, eventually, to work with him and his elite-level lifters and athletes. The heuristic was probably, let him in and if he works out we will keep him if not, we will throw him out. George Halbert had introduced us, and I’d just come off a raw bench press meet where I’d won the coefficient. At a bodyweight of 247 lbs, I pressed 500 lbs and then 540 lbs (see video below) as if they were empty barbells—not bad for a bodybuilder in the off-season.

But I failed my final lift of 570 lbs and looked like a fool doing so. I learned a lot from that failure. My main focus before the lift was the 'rack' command. I didn’t want to rack the bar too early after completing the lift and get a successful lift disqualified. With only 8 weeks of powerlifting training, I wasn’t used to waiting for the 'rack' call—I’d always racked immediately after completing the lift in training.

George Halbert and Drex Welch were there with me.2 George told me to pick a light opening weight, so I chose 500 lbs. As I held the barbell before lowering it, I remember thinking: Is this really 500 lbs? It felt light—almost like it was floating. It was my first time in 8 weeks with a barbell that didn’t have bands or chains. I smoked the lift, and I could feel the room’s attention shift—the loud Detroit Barbell Club went quiet.

After that, George asked how it felt, and I told him it didn’t feel heavy. The bar had 100 lb plates instead of the 45 lb plates we trained with, which made the weight more compressed.3 More notably, there were no bands or chains. It sounds crazy, but it literally felt like the barbell was just floating—as if I were bench pressing on the moon.4 George, never one for extra words when there was lifting still to be done, just nodded.

Drex, who always handled George’s lifts, helped me with my lift-off. For experienced lifters, the lift-off is an art—Drex had mastered it, placing the bar in my hands like it was a newborn.

The 540 lbs felt just as light, so I figured 570 lbs was a sure thing. Before my final lift, Drex must have thought so, too, because he got my attention and reminded me, “Don’t rack it until the judges say ‘rack.’” My inexperience with maximal weights, combined with Drex’s comment, had me focused more on not racking too soon than on the actual lift. I was cocky, not confident.

I lowered the bar onto my chest just as George had trained me, 'dropping'5 it right onto my sternum. When I heard 'press,' I drove the barbell up violently, so fast that it got out of my control. Halfway up, I lost control of my left arm position, my elbow suddenly shifting into an awkward angle before the weight came crashing down onto my chest. Drex grabbed the bar, and together we lifted it easily back into the rack.

Drex looked at me with concern, asking if something was wrong—thinking I must have injured myself. When I told him I was fine, he looked puzzled. As George’s long-time training partner and an elite powerlifter, he probably couldn’t imagine any other reason for missing the lift the way I did. Once it was clear I wasn’t injured, the embarrassment of missing the lift due to a lack of focus—and the feeling of letting down my training partners—started to sink in.

I should note this meet was hosted by the YMCA on the west side of Columbus, just a couple blocks up from my high school and also Westside Barbell. And not only was I not hurt, but the following day I wasn’t even sore and went right back to training.

A few weeks later, smoking cigars with George, he asked me what happened. I’d been haunted by that lift. I told him I’d been cocky, lost focus, and apologized for embarrassing them at the meet by not meeting the standard.6 Talking it through with George enabled me to realize I hadn’t trained with the Max Effort Method nearly enough. My neurology (CNS) didn’t have enough experience to control maximal weights under pressure at the level of competition—I’d survived max-effort training, but I hadn’t thrived in it.7 Years of bodybuilding had conditioned me for higher reps, training my nervous system for prolonged exertion and training through biological discomfort rather8 than the instantaneous exertion of a single lift.9

Failing that last lift and letting down my training partners still hurts to this today. But as Louie quote goes, this failure was a necessary milestone for me. I learned the hard way of the importance of regular max-effort work because athletes need their nervous systems to compress and focus for brief periods, especially at the level of competition.10 It’s better to look like a fool in the gym or clinic than to choke when it counts—but you have to feel it for yourself to understand, as Taleb says: scars signal skin in the game.

Looking back, I realize Louie respected me for not being afraid to look out of place, fail, or even look like a fool as a bodybuilder at a bench meet. I’d never learned as much as I did in those 8 weeks of training with George Halbert—I was hooked for more. In time, Louie allowed me not only to treat him but also to train at Westside Barbell. Even though I was primarily training for bodybuilding, I seized the opportunity and told myself I would learn as much as possible—and learn I did.

Note on Video: The recording captures a discussion with Jim Seitzer on resonance and barbells. We’ll release more of the recording to founding members in 2025, as it documents our research into resonance within connective tissue architecture, bands, and barbells. When Jim says 'prior to this,' he is referring to his understanding of his BandBell barbells until we introduce to him the concept of resonance.

Don’t Let the Fear…

Of looking inexperienced or foolish stop you from trying new, evidence-based training methodologies. There’s uncertainty in what we do, and trial and error is a necessary strategy.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Absolute: The Art and Science of Human Performance to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.