Speed strength is one of the four fundamental physical capacities that we have identified as Point B — with Point B being the optimal physical state of the athlete to effectively practice/acquire skill(s) and compete in the sporting environment.

Speed-Strength

The 100-meter dash is the perfect sporting event to see what speed-strength looks like in real life. The event is an all-out race for 100 meters that lasts just under 10 seconds. Going all out means the race will elicit from the sprinter their maximal momentary effort. The intent of their effort will be to generate and exert maximal force at the highest attainable speeds while sprinting, which is the best true test of speed-strength in athletics.

From a speed-strength perspective, the best individual sprint performance is to watch Ben Johnson’s 9.79 in the 1988 Seoul Olympic Games. In the video below, you will see Ben, at the start of the race, generate a maximal magnitude of force and exert that force into the blocks to absolutely explode out from the start relative to his competition. After Ben’s initial explosion out of the blocks, you see him working to maximally generate force and exert that force with the intent to sprint at the highest attainable speeds. Give this video a watch a couple of times, as it is an impressive performance of speed strength.

Speed Strength Defined

Speed strength is the ability to exert maximal force during high-speed movement (Allerheiligen, 1994).1

Let’s break down the above definition so we can coherently understand what speed strength is, starting with understanding what is: the ability to exert maximal force? The ability to exert maximal force during high-speed movement starts first with the athlete possessing the ability to generate maximal force. The ability to voluntarily generate maximal force is the definition of maximal strength.

Maximal Strength is the maximal amount (i.e., magnitude) of force that can be [voluntarily] generated (Platonov 1997).2

The above definition of maximal strength makes it easy to see that the definition of maximal strength is, in fact, literally embedded into the definition of speed strength. For that very reason, we at Absolute understand speed strength simply as: maximal strength at the highest attainable speed during movement.

Speed Strength = Multifaceted Nervous System-Based Capacity

The ability to generate and exert maximal force (i.e., maximal strength) at the highest attainable speed during movement is a multifaceted, or more simply, a two-part nervous system-based capacity (see image below). Part one means the nervous system possesses the ability to stimulate and recruit the largest motor units, which control the fastest muscle fibers - why? Because the largest motor units innervate the fastest muscle fibers, and it is those fast muscle fibers that are responsible for generating the largest magnitudes of force in the shortest duration. Think of part one as the “strength” component and the second part as the “speed component” - meaning how fast can the nervous system stimulate and recruit the largest motor neurons. When these “two parts” are coherently generated and synthesized by the nervous system, what is generated is speed strength or, more simply: strength at optimal speed.

Maximal Strength = Prerequisite for Speed Strength

Understanding speed strength as: maximal strength at the highest attainable speeds during movement, enables us to arrive at the logical conclusion that maximal strength is the strength prerequisite for speed strength - both in training to acquire more speed strength and in generating sporting performances of speed strength. Simply, an athlete who possesses a suboptimal maximal strength capacity will be constrained in the training for and generating of speed-strength.

Understand: Ben Johnson was strong and fast. Carl Lewis, Johnson’s main rival at the time and who finished 2nd in the ‘88 Olympics, was just fast. A sprinter who is fast but not strong, like Carl, will hit a strength barrier - a neurological stagnation that will impact performance in negative ways.

Optimal Maximal Strength for Speed Strength

Johnson’s performance in the 100m enables us to know that he possesses an optimal level of maximal strength. How so? You can see from the start he generates and exerts the largest amount of force at the highest attainable speed relative to his competition out of the blocks. Johnson was so strong and fast out of the blocks relative to his competition that it was thought that he was false starting - meaning starting before all the other sprinters. Instant replay would be utilized for the first time ever in sprinting and would prove Johnson was, in fact, not false starting. Instead, instant replay confirmed how much stronger Johnson was relative to his competition.

On top of being obviously stronger and faster out of the blocks than his competition, once Johnson is up and sprinting, he hits no speed barrier - meaning he shows no visible signs of deceleration, only of continued acceleration! He is so strong it looks like he shot out of a cannon and only picks up speed until the end of the 100 meters.

When we utilize the 100m dash performance as a feedback loop to understand Johnson’s maximal strength capacity, it is evident he possessed an optimal maximal strength capacity for him to be able to generate speed strength. When we do the same for Carl Lewis, it is equally as evident that he possesses a suboptimal maximal strength capacity as 1. he does not get out of the blocks explosively, and 2. he clearly hits a strength barrier, making him just fast and weak relative to Johnson.

Training for Maximal Strength = Training for Absolute Strength

The “strength” component is acquired by training for absolute strength. At Absolute, we understand maximal strength as the strength capacity the trainee acquires through the training for absolute strength - which is why the training for absolute strength is a prerequisite if the athlete is to acquire Point B. But keep in mind that speed strength is multifaceted, and if the athlete was only training for absolute strength, they would end up hitting a speed barrier because of the amount of maximal amount of load needed optimally train.

Case in point, watch the training video below, and that will be the slowest you will ever see Ben Johnson move. It just so happens Johnson has 545lbs on his back, and his still moving it fast, all things considered. Also, take note, from a strength training for the barbell back squat, since Johnson got more than 1 repetition, the load of 545lbs is submaximal to him - meaning his true max (i.e., 1RM) has to be somewhere over 600lbs.

Speed “Strength”

Speed strength is a “strength,” so in order to optimally train to acquire more of it, the athlete must possess adequate maximal strength levels - hence, why we stated earlier that maximal strength is the prerequisite strength capacity of speed strength. Think of training for speed strength as training work that converts maximal strength, which generally moves slow (i.e., strength speed), into strength at faster speeds - more specifically, the highest attainable speed.

Ben Johnson utilized the back barbell box squat to train to acquire and sustain maximal strength - the ability to generate force. He then concurrently utilized sprinting at different intensities with different intents to convert his ability to generate maximal force to be able to generate and exert maximal at the highest attainable speed throughout the length of 100 meters. Remove the maximal strength training, and Johnson is only fast but not fast and strong - he then becomes second-place finisher, Carl Lewis.

Training for Speed Strength

All of Exercise Science agrees that intensity is what governs strength adaption (i.e., training effects).3 Therefore, if we are to optimally train for speed strength, we need to be able to optimally control training intensity. At Absolute, we utilize the maxims of strength to control intensity. The maxims of strength are: Load, Effort, and Intent.

The maxims of strength will not be new to FRS strength coaches, as the maxims of strength are what optimally constrain the training intensity for the FRS Internal Strength Model for all of the biological elements responsible for strength at the internal level.4 Those same maxims we will utilize here, but instead at the external level to optimally control intensity to elicit training effects that enable the athlete to generate maximal force and exert said force at the fastest attainable speeds.

Training Environment for Speed-Strength

When training for speed strength, it is the coach’s responsibility to put the athlete in a training environment where he/she can learn how to generate maximal force at the highest attainable speeds. The only way for the strength coach to create the training environment for speed strength will be to optimally align the maxims of strength to do so.

Load

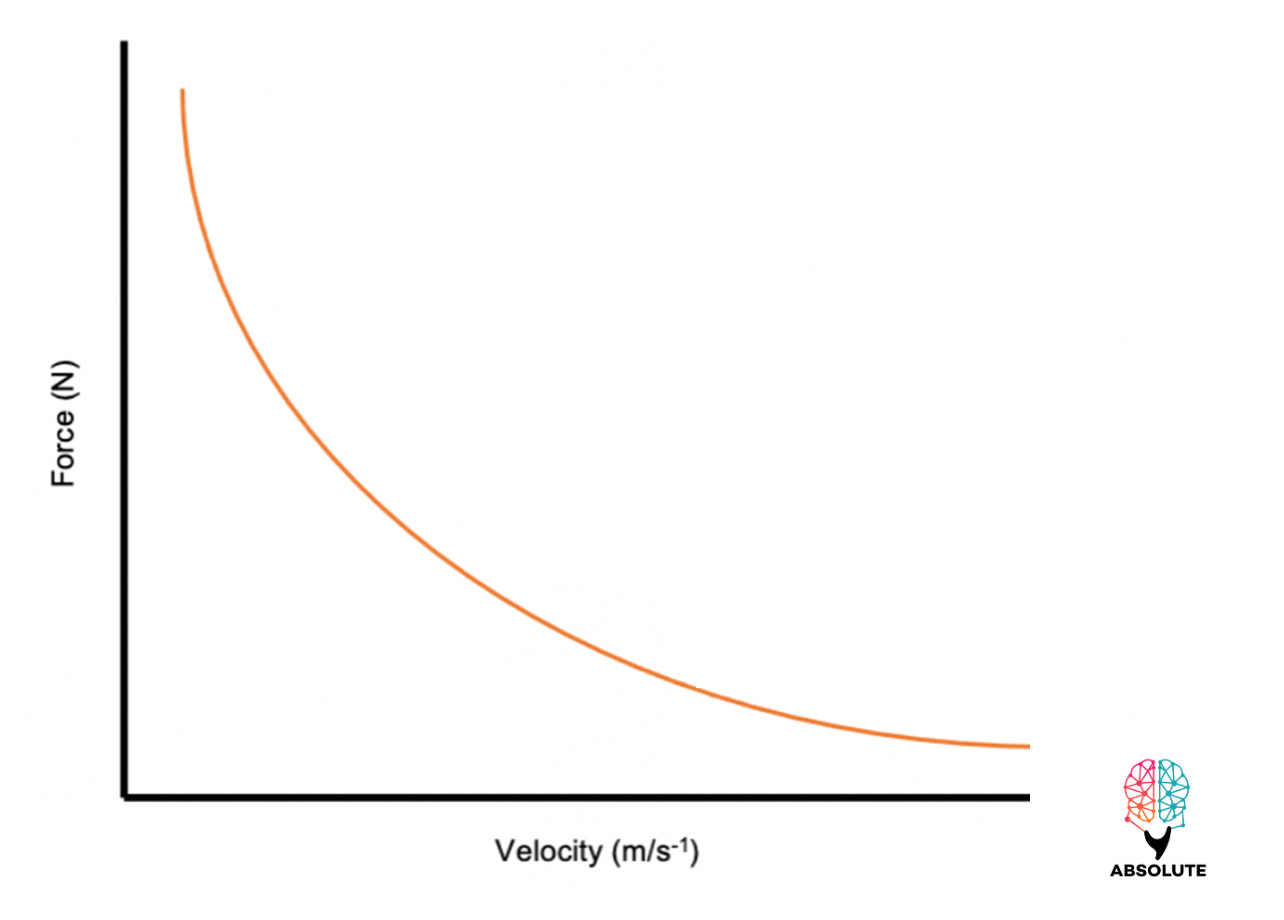

Submaximal loads are utilized in the training of speed strength - why? Because if maximal loads are utilized, externally, the athlete will not be in a position to move at optimal speed (i.e., the highest attainable speed). The force-velocity relationship/curve, pictured below, enables us to know with certainty that when force is high, velocity is low, and when force is low, velocity is high. Velocity is speed + direction, and speed is what we are after - therefore, we utilize submaximal loads but have the athlete move them at optimal speed.

Effort

Because the load is submaximal, the effort will also be submaximal. Simply meaning: speed strength training work will not elicit the maximal momentary effort from the trainee. This training work is stimulating but not fatiguing to the point of decreased acceleration - as that would be training deceleration. To combat deceleration, strength coaches have utilized tendo units - which we strongly recommend and suggest.

Intent

The intent of the athlete is to move the submaximal load they are training with/against at a dynamic effort - which means moving at the highest attainable speed.

The constraining of conscious intent to move and exert maximal force at the highest attainable speed is what will allow the athlete to stimulate and recruit the largest motor neurons and fastest muscle fibers to do training work against a submaximal load - as normally, the largest motor neurons and fastest muscle fibers are only stimulated and recruited with a maximal load or the training for absolute strength. When the largest motor neurons call upon the fastest muscle fibers to move a submaximal weight/resistance, that weight or resistance will move at the highest attainable speed - which is the sole aim of this training work!

Understand: If conscious intent was not constrained to move at the highest attainable speeds, the motor units and muscle fibers; this training is targeting would not get optimally trained.

Speed Strength Training Work

Simply, speed strength training work is the athlete training with the conscious intent to move a submaximal load at the highest attainable speed. In the Science and Practice of Strength Training, this strength training method has been identified as: the dynamic effort method (i.e., DE).5

Understand: DE is not utilized to increase maximal strength but to improve the rate of force development (i.e., speed).6

Amplifying Speed Strength Training Work: Accommodating Resistance

An elite-level powerlifter and founder of the Westside Barbell Club, Louie Simmons, is accredited with taking DE strength training work to another level with the addition of accommodating resistance via bands and band tension.7 We will delve more into accommodating resistance in another article, but for now, it is important to comprehend that the purpose of training with bands is to create overspeed during the eccentric phase of the movement, which in the subsequent concentric phase can almost totally reduce bar deceleration.

Training for Speed Strength = Concurrent Training

Training for speed strength requires concurrent training (i.e., conjugate method) - meaning the athlete must train to get faster and stronger at the same time. Recall and coherently understand: an athlete that does not train maximal strength will hit a strength barrier when doing their speed strength training or performance - as they will lack optimal strength. Inversely, an athlete that does not train at the highest attainable speeds will hit a speed barrier, as their nervous system will generate and exert maximal force, but at suboptimal speeds. Thus, speed strength training requires strength and speed to be trained in parallel (i.e., simultaneously). More simply, this means the coach must utilize conjugate method programming - not linear block periodization.

Ben Johnson’s Skilled Performance

Possessing the ability to stimulate and recruit the largest motor neurons to call upon the fastest muscle fibers to generate maximal force and to possess high functioning joints and connective tissue to be able to exert that force at the highest attainable speeds is the generation of speed strength - and it is also skilled human performance.

More on Ben Johnson’s 9.79*

Still, to this day, there is a lot of controversy over the Olympic Games, where Johnson ran his 9.79. There is an asterisk after the 9.79 because following the Games, Johnson tested positive for and later admitted (although may have been persuaded to admit) to using banned performance-enhancing drugs in his off-season training. Johnson claims to this day that his tests at the Olympic Games were tampered with and were a false positive. Even more controversial was Carl Lewis, the second-place finisher in the off-season who tested positive on multiple occasions for performance-enhancing drugs. Watch the ESPN 30 for 30 on this event and form your own conclusions as to what all occurred - it is a great documentary.

works cited

Simmons, Louie. Special Strength Development for All Sports. Westside Barbell, 2015.

Kurz, Thomas. Science of Sports Training: How to Plan and Control Training for Peak Performance. Stadion, 2001.

Zatsiorsky, V. M., Kraemer, W. J., & Fry, A. C. (2021). The Science and Practice of Strength Training. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Quint, John. (2021). Internal Strength Model: Training Intensity: Maxims, Ecology, and Efficiency [Lecture]. Toronto, Canada: Functional Anatomy Seminars.

Zatsiorsky, V. M., Kraemer, W. J., & Fry, A. C. (2021). The Science and Practice of Strength Training. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Zatsiorsky, V. M., Kraemer, W. J., & Fry, A. C. (2021). The Science and Practice of Strength Training. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Siff, Mel Cunningham. Supertraining. Supertraining Institute, 2004.

In the article you were talking about the tendo unit. I’m looking for velocity-based equipment to work with (but never worked with something like it before). I was wondering is there is a specific preference for using the tendo unit in comparison to gymaware (or other brands)?