The Psychology of Training: Understanding Training Risk: Part 1

What Seems like Risk Can Lead to Eventual Payoff for High Performance

Achieving high performance in sport, let alone anything, is difficult. It requires endless motivation and a relentless pursuit of what is possible. To many, achieving high performance requires gathering small wins over a long period of time in a cumulative way that allows gains to be continually added upon in a linear fashion.

Although this sounds very logical, in reality, it is far from the norm, as nothing is as linear as it seems. With respect to human performance and the training for it, this is especially true. The acquisition of the physical capacities required to compete at high levels must occur with an understanding of risk and how it applies within this context.

A Market Analogy

To draw an analogy to discuss risk, let’s discuss the very basic structure of finance. As we know, what is commonly referred to as the market is the largest complex system in the world. I am going to assume that most of us, if not all of us, have some form of capital invested in the market for long-term purposes, the most significant being retirement. I am also going to assume that most of us who do have money invested in the market have it structured in a very particular way that lines up with traditional thinking on how to do this.

This traditional thinking has been around for a very long time and is often referred to as Modern Portfolio Theory which was initially conceived of in the 1950’s, roughly around the same time that our interpretation of modern strength training was. Modern portfolio theory dictates that everyone’s investment portfolio should consist of a certain percentage of stocks and bonds so that over longer time frames, the portfolio will generate high returns, while ultimately limiting or reducing the amount of risk taken on by the individual in the market.

This is the strategy of any and all investors; maximize returns and minimize the amount of risk taken to do so. Hopefully, you see the parallels in training for strength.

Is Diversification the Way to Maximize Return?

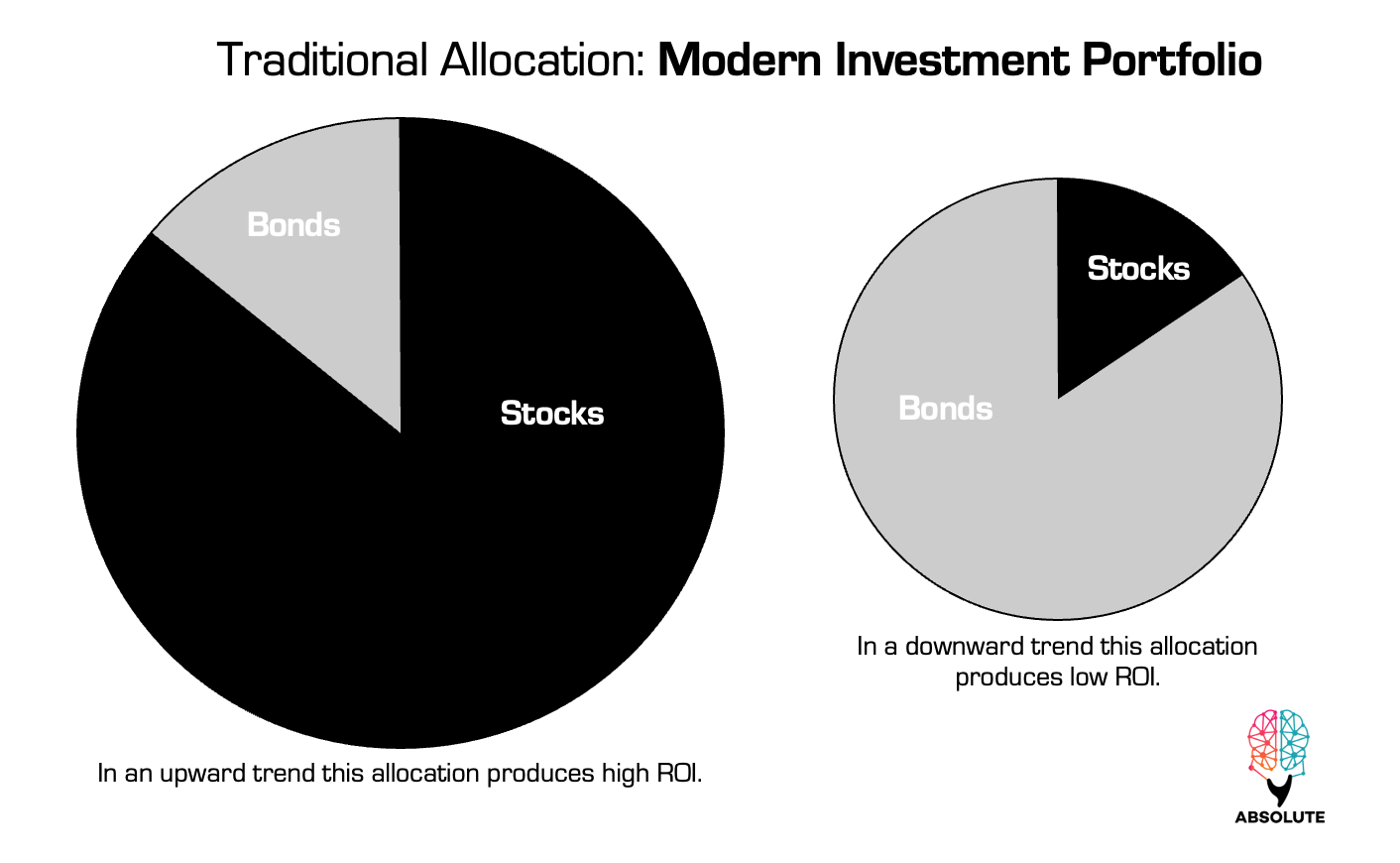

Generally, and for ease of this discussion, this falls into something along the lines of 60% stocks and 40% bonds. Stocks have higher yield capability, bonds have lower yield capabilities. Pretty simple. Stocks will make you more money but also have the potential to cost you more at any point in time. The point is that with this type of allocation, the person who holds this type of portfolio would be able to manage the risk that comes with having money in the market as these two things would “balance each other out” as they usually go up and down in different directions depending on interest rates and the state of the market, whether it is bullish or bearish.

Considered in isolation, neither of these two pieces of pie are considered appealing because they wouldn’t give you what you want from a returns perspective, however by combining the two together in a more holistic way, the risk of stocks is counteracted by the overall less risk of bonds in an attempt to ensure the maximum possible return over time. Essentially this portfolio is a buy, hold, and wait strategy that puts much of the possibility of return in the hands of the market.

This is the simple process of diversification that spreads invested capital across different asset classes. The logic is that the more you can diversify, and not keep all your eggs in one basket, but spread them over many baskets, the more eggs you may have at the end if one of those baskets gets dropped and the eggs break.

Herein lies the problem with diversification in general. Counter to its logical interpretation, spreading out assets to effectively attempt to reduce the overall amount of risk, it fails to account for the fact that all risks are not created equal. Every investment, whether financial or otherwise, like time in training, comes with a specific level of risk to the individual who is investing the capital. It is important that this is considered as risk is relative. As Mark Spitznagel, the head of Universa Inc., one of the world’s most successful hedge funds, says, “Diversification is a dilution of risk it is not a solution to it.”1

Here is why diversification as a concept has flaws. As we know, there is a lot of oscillation within the market. Therefore, the major issue with this traditional line of thinking is that it is great when the market is high because the returns in both asset categories will be high, especially within the stocks, as they will generate a large yield - which you see with the graph on the left. However, it isn’t so great when the market drops, causing a large decrease in wealth due to stock allocation, as the bonds will never outweigh the losses in stocks, and as a result, the net effect is that the portfolio gets much smaller.

Returns Fallacy

This leads to the returns fallacy, again a large misunderstanding of the perceived trade-off between return and risk. It begins by assuming that all systems are optimal and efficient and that investing in capital is the repetitive act of picking the investment opportunities that allow for the highest rate of return (remember, nothing is linear!). This is perhaps a bias or fundamental flaw in modern investing as well as modern strength training, where the fallacy becomes similar in that the concept of building strength or any other physical capacity is simply the choice of performing the exercises that are thought to have the highest returns on the expected outcome. This simple summing of the expected rate of return based on thinking the market is efficient will never protect you when it crashes.

The other part of the fallacy is that higher rates of return can only come with a higher tolerance for risk, which sounds logical, although it is never sustainable for any length of time. The market is volatile, much like sporting or performance environments, and this volatility is dependent on many factors that are out of our control. Even though this is the case, volatility can be protected against.

It should be pointed out that many people have succeeded using modern portfolio theory to build wealth, as have many people succeeded using the modern interpretation of strength training to get measurably stronger. To this point, modern strength theory has attempted to build the quality of strength as a measurement, without necessarily understanding the volatility of the environment within which strength must occur. This concept of strength has allocated that all strength training must occur very similar to the environment that it is expressed in, and so we have allocated a percentage that is similar to Modern Portfolio Theory (60 % accessory work, 40% major lifts) to achieve this. This is the traditional tradeoff. This again stems from the underlying assumption that the variables of the environment, whatever that environment might be, can be controlled and are efficient. It also presumes that we can only gain strength by doing the required lifts that have been traditionally used to get that strength in a simple process of diversification.

It is easy to see historically, either in your own training or that of your clients, that when there is an uptrend (all variables align), this systematic allocation generates large returns in performance (a feat of strength). The other side of that sword is that when those variables don’t align, it can lead to huge losses that limit the opportunity for growth leading to plateaus and stagnation. So what we often see with this allocation is a longer drawn-out increase in the measureable qualities of strength because of the unpredictable nature of strength training.

As a result, of trying to control for as many external variables as possible, many smart scientists and coaches have attempted to fine-tune the standard allocation by adding small chunks of different strength training as well as other types of training means in an attempt to diversify the allocation in more detail. Why? Again, just like with our diversified portfolio, in an attempt to minimize downside risk.

These percentages are not concrete obviously, and are just an example of such allocation, as there are many different iterations. What you see is that this percentage breakdown allows for other means to enter the portfolio, thereby causing the big lifts and accessory lifts which are the major components, to come down in percentage with the thought that this will allow the trainee to undergo the maximum amount of return (training based adaptation) with the minimal amount of negative effects due to the large amount of diversification within the program and not solely training within one chunk of the pie.

Although this is very well-intentioned, this does reach a threshold. The more the pie gets chunked and manipulated, the less return can be achieved from each chunk over different time frames. This means that less returns from each chunk lead to less overall training effects. It may seem illogical because of the grander attempt at diversification, which seems prudent; however, this is just a more complicated breakdown of the initial portfolio, which focuses on matching the market to the portfolio instead of the portfolio to the market. In strength training, this has drastic implications. This leads to loss, more often than not, in the form of injury due to the law of diminishing returns.

To reiterate, the environment in which strength must be expressed is not a controllable one. It is constantly changing, and therefore our assumptions about how it works and how one can prepare for it are flawed. From an ecological point of view, it is fair to say the majority of risk occurs in the sporting environment at the Level of Competition, where numerous external variables that are inherent at this level cannot be controlled or accounted for (like the market). When the predictability of the environment and the probability of occurrences within that environment cannot be intelligently and systematically controlled, the risk of that environment increases.

Is there a way that we, as strength practitioners, can manage risk for our athletes and train ecologically?

Yes.

In Part 2, we'll explore specific training strategies that achieve both objectives. Subscribe now to receive the valuable strategies directly in your inbox when we release Part 2.

Safe Haven. Investing for financial storms. Mark Spitznagel.

Fantastic analogy and comparison of the Market and Training.

Great read. Thanks.